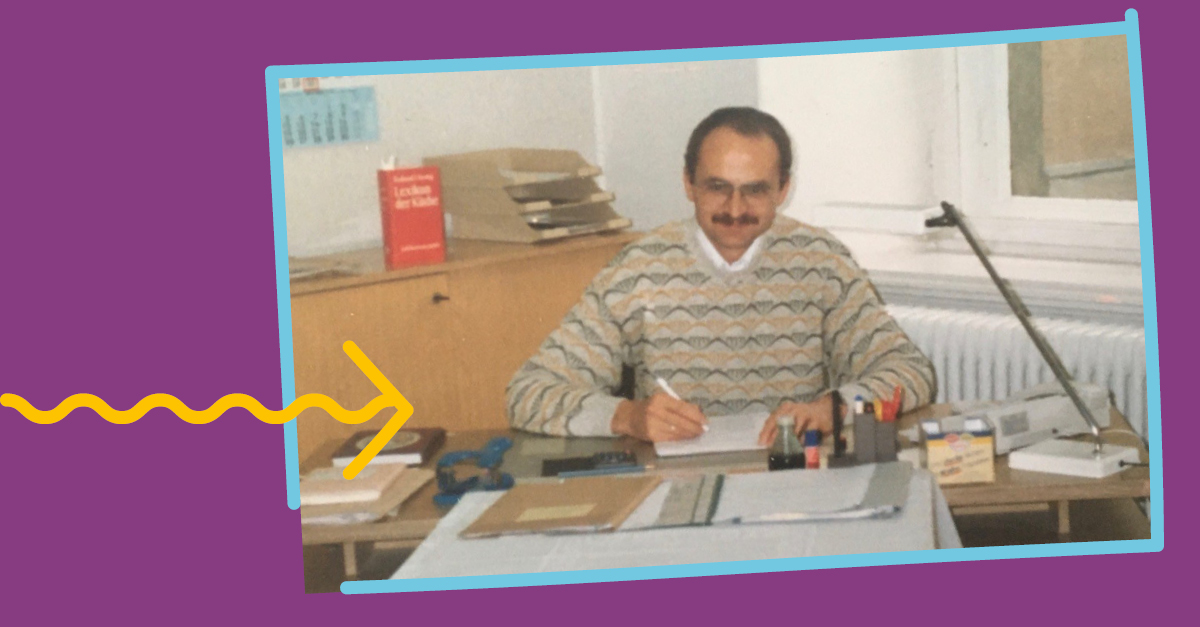

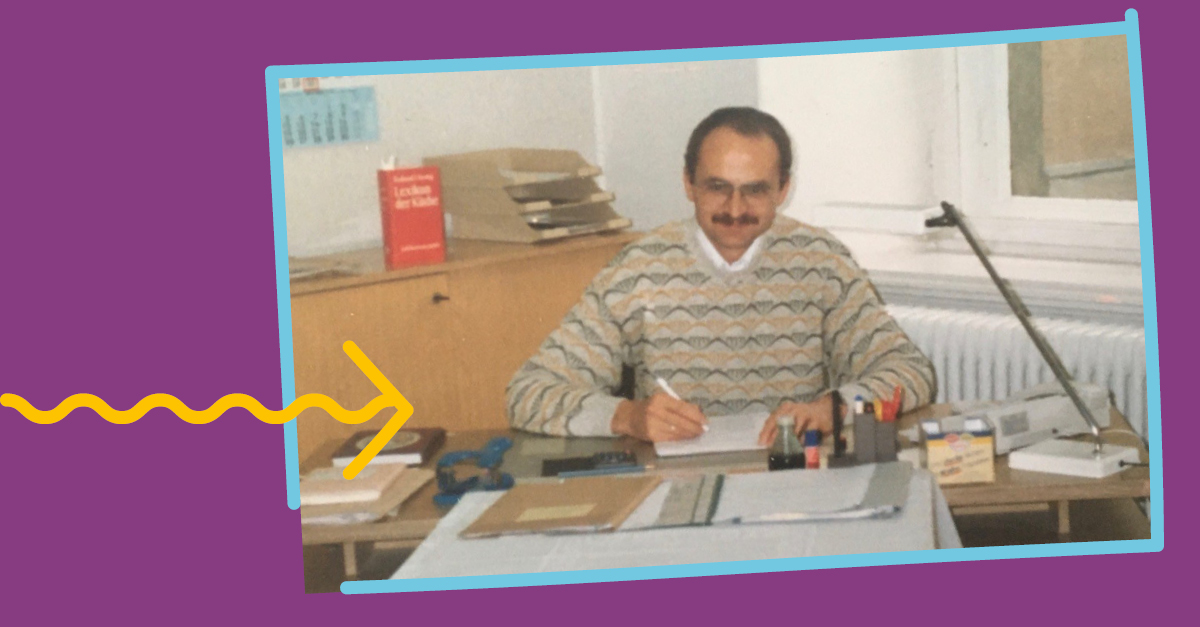

About food stamps, export beer and the art of improvisation: A contemporary witness report by our long-time employee Gerald Hoffmann.

About food stamps, export beer and the art of improvisation: A contemporary witness report by our long-time employee Gerald Hoffmann.